Ocnus.Net

The Actual Reasons The Electoral College Exists

By Brendan Donnelly, Weird History, 13/1/20

Nov 22, 2020 - 12:41:12 PM

Every four years, the whole world stops to watch the United States presidential election. And every four years, we as a global collective ask, "Wait, what's going on? Hold up, this candidate got the most votes - shouldn't they be the winner? What do you mean Florida's vote is more important?" Yes, unlike any other democracy in the world, the most powerful office in the US is beholden not to the popular vote, but to 538 select voters dubbed the Electoral College. The complex system has led to some of the most surprising election victories in history, and its function continues to elude foreigners and US nationals alike - so why does the Electoral College exist?

Well, the answer isn't simple. The nation's Founding Fathers debated a plethora of problems when ideating this new form of democracy - potentials for corruption, the destructive nature of political factions, and the undeniable capacity for large crowds of people to get swept up by populism, among many others - and the Founding Fathers tried their best to create an institution that guaranteed democratic governance over tyranny. But even with their best efforts, they weren't flawless, and neither was the government they created. The systems, beliefs, ideals, and the people who created them were often acting in contradiction; for example, the Electoral College was just one of many methods of rationalizing and balancing the ideals of democracy in a nation that was still largely reliant on the institution of slavery.

The United States, and the world as a whole, has changed dramatically since 1787 - so why do we still abide by a political system that has largely gone unchanged for the last two and a half centuries? There are both good reasons against the Electoral College and good reasons to keep it, but what ultimately stops the country from replacing it or simply making minor adaptations is that the current system benefits those who have the power to change it.

Voters Aren’t Actually Voting For The President

-

The presentation of any presidential election is fairly misleading, though justifiably so. Whether they're bumper stickers, flags, or signs that litter some people's front yards, the instructions to "Vote for X presidential candidate" aren't technically in the power of the general voter. In truth, that power belongs to the 538 people who are selected by the states to vote for the country's president. When the general public votes, they're instead voting for one of those 538 people, who will then vote for the presidential candidate who hopefully best represents the interests of their entire electoral district.

According to James Madison in Federalist No. 39, the intent of the process is for the president to be "indirectly derived from the choice of the people," and the constitution he drafted perfectly aligns with his intention of an indirect democracy.

Under the US Constitution Article II Section I, the president is elected through a number of electors selected by the states through whatever means the respective state has chosen. But no standard was ever defined by the federal government for electors beyond the stipulation that "no Senator or Representative, or person holding an office of trust or profit under the United States, shall be appointed an elector." The only other clause restricting who could be an elector was introduced in the Fourteenth Amendment, which was added to the Constitution after the Civil War. The clause it added, however, is that an elector couldn't have participated in rebellion against the United States or aided an enemy.

In essence, the general population isn't voting for the presidential candidate they see on their ballots, but instead voting for a most-times-unnamed person (or group of people) who is neither an already elected federal government official nor a rebel. The person selected through this obscure process requires voters to put their faith in the hopes that the unknown elector will select the presidential candidate the voters want. When it's all said and done, it's much easier for everyone to think about their votes as a vote for their preferred presidential candidate.

-

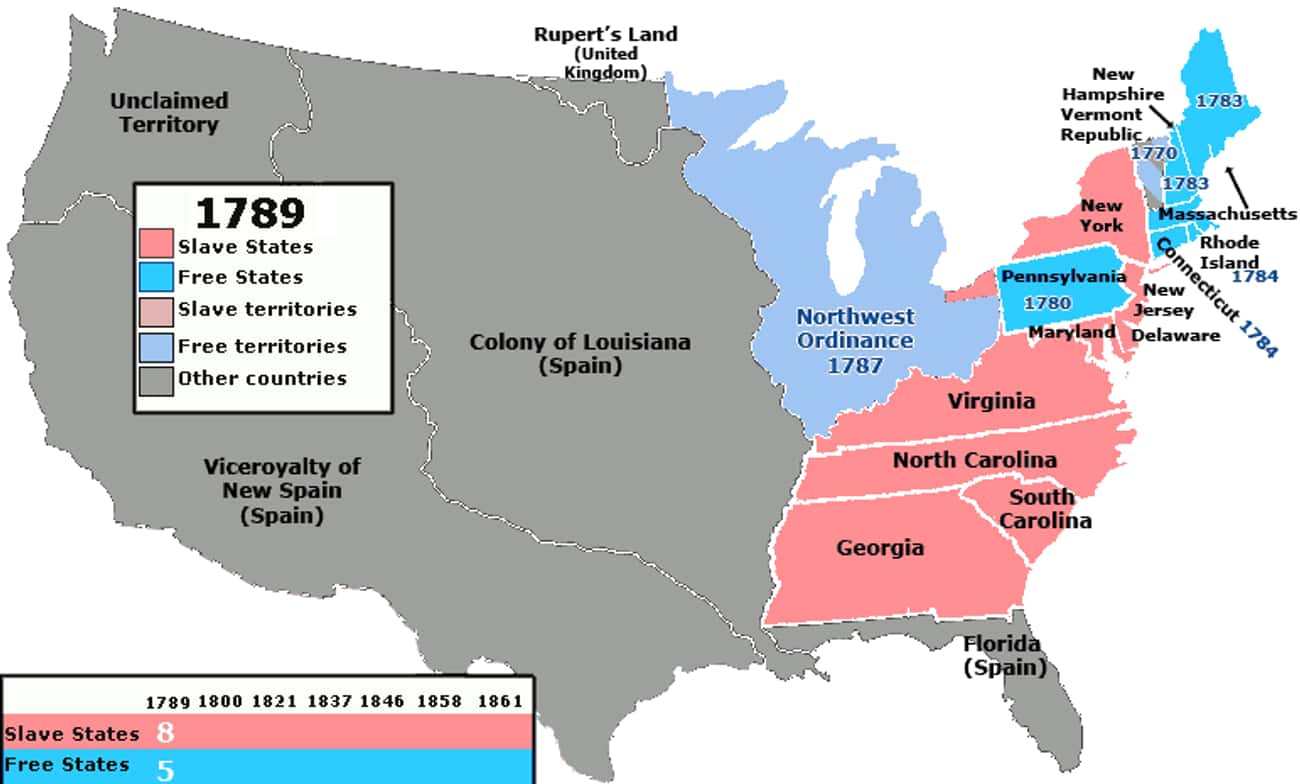

The Institution Of Slavery Made It Impossible To Have A President Elected Through The Popular Vote

Despite the fact that the electoral process selects the president of the United States, news outlets, political parties, and the general public still like to keep track of the popular vote. The popular vote, however, is, for all practical purposes, meaningless. In fact, there have been five presidential elections in US history in which a presidential candidate has lost the popular vote but won the election.

But if the intention of the Founding Fathers was to create a representative democracy, why would they not select the president by simply surveying everyone's opinions rather than through a confusing and convoluted system?

Well, the Founding Fathers also debated that question. In fact, the drafter of the Constitution himself, James Madison, preferred selecting the president through the popular vote. "The people at large was," he wrote, "the fittest in itself. It would be as likely as any that could be devised to produce an Executive Magistrate of distinguished character." There was a major problem, however, that sullied the entire Constitutional debate: the institution of slavery.

Earlier in creating the Constitution, both the Southern representatives and the Northern representatives debated adamantly as to whether or not the institution of slavery should exist at all, and if it were to exist, whether enslaved people would have representation in the government. Both sides finally came to a compromise when instituting the legislative branch. Slavery was legal, but only in certain states and territories. Enslaved people, however, could not vote, but they counted as three-fifths of a person when determining how many congressmen in the House of Representatives a state should have.

In Madison's opinion:

There was one difficulty, however, of a serious nature, attending an immediate choice by the people. The right of suffrage was much more diffusive in the Northern than the Southern States; and the latter could have no influence in the election.

Enslaved people made up a large proportion of the population in the Southern states. In fact, almost 50% of the South Carolina's population was enslaved in 1790, and the enslaved population only continued to grow.

Rather than try to negotiate the problems prompted by slavery, Madison believed "[t]he substitution of Electors obviated this difficulty, and seemed, on the whole to be liable to fewest objections."

-

It Was Partially Intended To Restrict The Effects Of Popular Factionalism And Corruption

One of the largest fears the Founding Fathers had of a direct democracy was factionalism, and reasonably so. James Madison specifically defined factions as "a number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or a minority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adversed to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community." Factions were common among historical democracies and were partially at fault for the demise of ancient Athens and the Roman Republic.

Learning from these past instances, Madison knew it would be a counter-intuitive endeavor to prevent factions despite how much he (or George Washington in his farewell address) warned of their danger to democracy. Preventing factions, Madison figured, could be done in only two ways: "by destroying the liberty which is essential to its existence" or "by giving to every citizen the same opinions, the same passions, and the same interests." Both those solutions, however, were more problematic than factionalizing.

Madison devised ways to control and limit the effects that factionalism has in an open democracy. One tactic was the Electoral College. By dispersing the electors and instituting representatives from different states, and among them representatives from different districts and regions, the Founding Fathers sought to limit the powers a demagogue, populist mob, or even a cabal could have over the electoral process.

The Founding Fathers, however, did intend for the electors to be able to judge and deliberate for themselves the character and qualifications of the candidates, rather than blindly follow the whims of the popular vote. In his paper The Mode of Electing the President, Alexander Hamilton states:

[T]he immediate election should be made by men most capable of analyzing the qualities adapted to the station, and acting under circumstances favorable to deliberation, and to a judicious combination of all the reasons and inducements which were proper to govern their choice [and the] small number of persons, selected by their fellow-citizens from the general mass, will be most likely to possess the information and discernment requisite to such complicated investigations.

-

The First Plan Was For Congress To Select The President, But It Was Scrapped

One of the key questions the framers of the Constitution needed to determine was the openness of the democratic system. This was assessed in order to stymie the potential corruption of political elites and to prevent the rash judgment of a populist crowd. Arguably, the Founding Fathers never found the right balance, but isn’t from a lack of trying.

Even in the case of the presidential election, the Founding Fathers played around and debated different possibilities, the first of which had very little popular involvement. Derived from James Madison’s Virginia Plan, the initial design was for Congress alone to determine and elect the president. It may seem counter-intuitive to have what may seem now to be a political elite determine the nation’s prime executive, but there was a rationale behind it. The framers were trying to build a democratic republic, a government which is ultimately a democracy but is actually governed by representatives.

The House of Representatives (with increasing representation based on total population) is meant to be representative of the people and their local communities. The Senate (with two representatives per state to provide equal power between large and small states) represents the states as a whole. The president, however, represents the entire nation and should act for its well-being.

The framers well understood that the common man may not have the national interest in mind, thus when determining a president, they may vote based on personal and local interests and passions. The House and Senate, however, work within the federal government to represent those local and state interests. Through debate, reason, and voting within Congress, the two branches could work out the interests of the people and the state among other representatives and supersede them with the interest of the nation as a whole.

When debating this system in 1787, however, multiple members of the Federal Convention pointed out that this system could easily breed corruption. The members of Congress, as the federal legislature, could use this system to elect a president who would work for their benefit as a class of political elites. Of course that system would not do. They were trying to build a system with strict checks and balances to prevent any branch of government from gaining too much power and instituting tyranny.

The Electoral College, however, was designed to solve the problem. The electors weren’t members of the federal government - they were individuals within the states whose interests weren’t necessarily political who were determined by the states to have the ability to choose the president for the national interest.

That’s not to say remnants of this old system weren’t left within the Constitution. In the case of a tie, the House is meant to select the next president.

-

Electors Were Designed To Have The Freedom To Reason And Decide Who They Thought Should Be The President

Despite having very few restrictions on who the electors were meant to be, the one rule the Constitution did provide is very important. The Constitution states in Article II Section I that "no Senator or Representative, or person holding an office of trust or profit under the United States, shall be appointed an elector." This reflects the intent of Alexander Hamilton (in Federalist No. 68) and James Madison (in the Constitution itself) to empower electors to express the will and act in benefit of the people they represent and the nation as a whole by keeping current federal government entities from filling the role.

Presumably, these individuals would have no ulterior intentions or vested interests in anything beyond the well-being of their constituency. According to Hamilton, they were to be "detached" from the government and would "enter upon the task free from any sinister bias," and they would neither have the time nor means to corrupt the process.

As made apparent by Alexander Hamilton's words, there was intended to be a close relationship between the electors and the constituency they represented. Electors were expected to understand the community they resided in and act in the specific interests of that community and the nation as a whole. "It was desirable," he wrote in Federalist No. 68, "that the sense of the people should operate in the choice of the person to whom so important a trust was to be confided."

-

-

State Legislatures Were Given The Power To Decide Who The Electors Were

Despite the intent of certain Constitutional framers, many of the states did not divide their electors among districts. The mode of selecting electors was never specified in the Constitution, and according to the Tenth Amendment, any "powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people."

States have expressed that right and tested a multitude of different methods over the first 50 years. During the first few elections, some states had electors who were selected by the state legislatures, giving no agency to the popular vote except when deciding their state legislatures. Other states, however, decided based on the popular vote in a winner-takes-all-manner. Still others split them up among districts. There was no consensus on what method worked best, nor was there agreement as to what ends they were trying reach.

As thirteen presidential elections passed, state methods for elector selection kept evolving. One, however, proved so popular and effective for the states (and the political parties in those states) that by the election of 1832, every state but South Carolina (who later changed in 1868) was using it. As a result, the winner-take-all method remains the norm today.

In every state besides Maine and Nebraska, the state allots a slate of electors to the candidate who has won the popular vote within that state. The slate of electors, who are meant to represent the people of that state, however, aren't actually selected by the people - they are selected by the two major political parties. The Republican Party within the state selects a slate of individual electors who it knows will vote for the Republican candidate, while the Democratic Party does the same for its candidate. When voting for the presidential candidate, the state's popular vote is in fact voting for which of the two slates of electors they want.

-

There Is No Federal Law Mandating The Electors To Follow A State’s Popular Vote

One aspect of the Electoral College that may stand apparent is the fact that there are no federal laws mandating how electors should vote in the case of a popular vote. Electors rather pledge for whom they will vote, and those who do not follow their pledges are known as "Faithless Electors."

Granted, the Founding Fathers did imply that the system was not meant to be made through popular decision but through the decision-making of a select few, hence the reason the United States has a complex Electoral College instead of a popular vote. Most states individually implemented a winner-take-all system informed by the popular vote, and the major political parties determine who the electors will be if the popular vote determines their candidate should be elected. There is absolutely no constitutional guarantee that the selected electors will follow the decisions made by the state’s popular vote or the political party that selected them.

In fact, it is directly supported by the Federalist Papers that the electors should have sole power over their votes and should determine them based on their own reasoning:

The immediate election should be made by men most capable of analyzing the qualities adapted to the station, and acting under circumstances favorable to deliberation, and to a judicious combination of all the reasons and inducements which were proper to govern their choice. A small number of persons, selected by their fellow-citizens from the general mass, will be most likely to possess the information and discernment requisite to such complicated investigations.

But few electors throughout the nation's history have actually expressed this constitutional right. The first case was in 1796, when a Federalist elector voted for his political opponent Thomas Jefferson despite pledging to vote for his party's candidate John Adams. In 1872, 63 Democratic delegates refused to vote for their candidate Horace Greeley because he passed before the Electoral College was able to convene. In 2000, a delegate chose to abstain rather than vote for the two candidates. In 2016, multiple electors, unsatisfied with the candidates their party had nominated, instead voted for third party candidates.

There have been others over two and a half centuries, but in each case, the faithless elector made no difference in the outcome of the election. Thirty-two states and the District of Columbia, however, still have faithless elector laws in order to prevent it from happening.

-

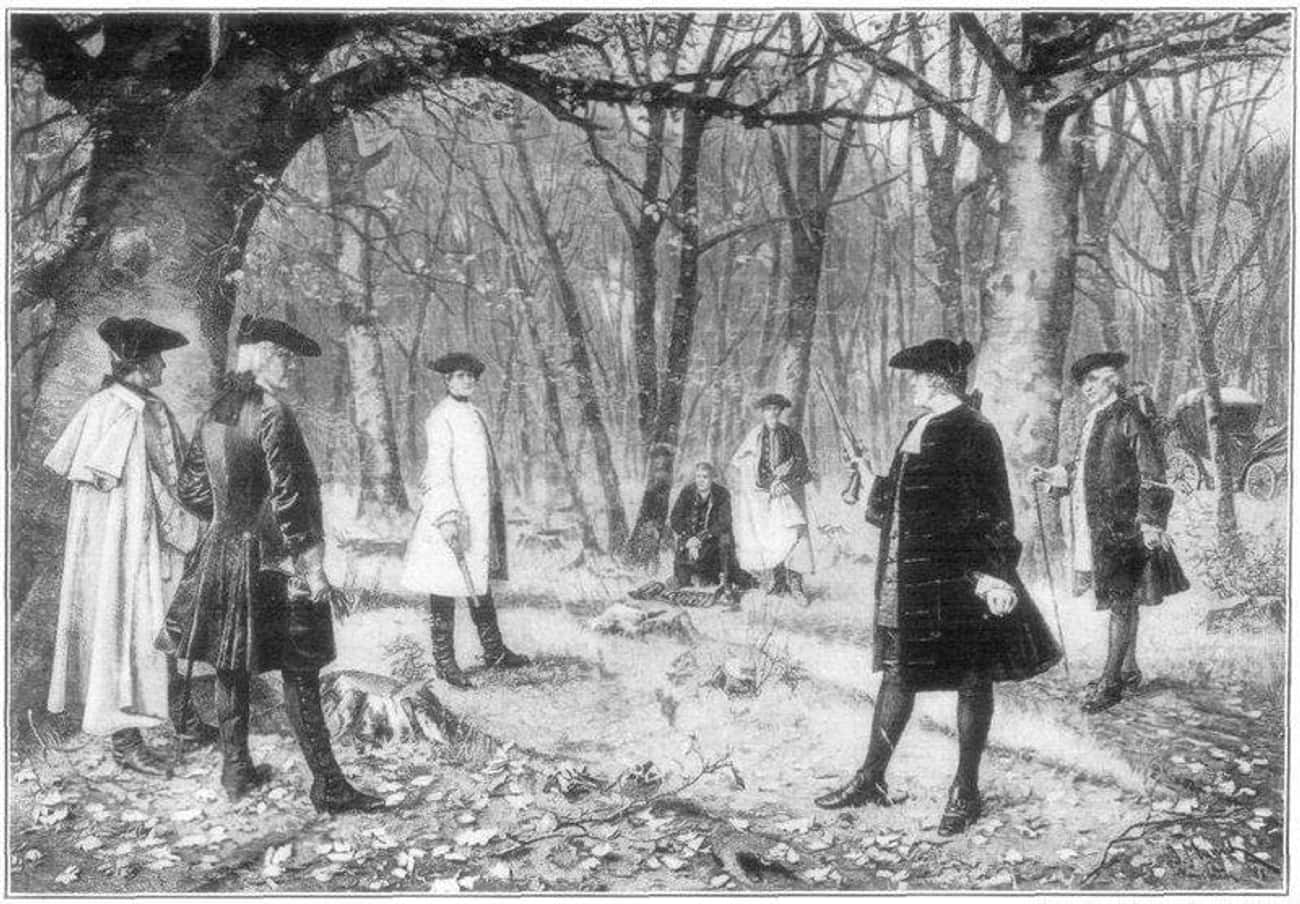

Hamilton Drafted An Amendment To Fix The Problems Of The Electoral College, But Passed Before He Could Finish

It was fairly obvious to a couple of the framers of the Constitution from early in the nation's history that the Electoral College system had its fair share of problems. By the election of 1800, only 13 years and three presidential elections after the Constitution was ratified, the Electoral College system began to breakdown in the face of aggressive and contentious political campaigning.

The candidates and others heavily involved with the American government believed they were fighting for the true character and heart of the nation. Presidential candidate Thomas Jefferson believed the incumbent, President John Adams, was becoming increasingly tyrannical and that the Federalist Party wanted to reinstitute British colonialism over the new nation. Alternatively, Alexander Hamilton and the Federalist Party feared Jefferson and the Democratic-Republicans would try to dismantle the power of the federal government.

Within this air of mistrust and contention, the election of 1800 was a disastrous mess of personal attacks and cunning politicking. Most notable in the case of the Electoral College, however, was the institution of the winner-take-all method to ensure a victory. For example, in Virginia, Jefferson's home state, the Democratic-Republicans held a majority. But as of 1798, eight of the 19 congressional districts within the state held a Federalist majority. Rather than risking eight potential electors to the Federalists, and potentially losing the election, the Democratic-Republican-held state government changed its method of elector selection to the winner-take-all method. This guaranteed Jefferson 21 electors. In response, Federalist majority states decided to change their system to allow only the state legislatures to choose the electors. Despite Federalist efforts, however, Jefferson and his running mate Aaron Burr won the election.

Whether it was due to an understanding of how problematic and partisan this system was, or because he was angered by the political loss he suffered, Hamilton drafted an amendment to change the presidential election. In it, he offered multiple changes, notably a proposition that would make the congressional-district method the legal standard across states. The resolution was never presented. Alexander Hamilton drafted it in January 1802, but he perished in 1804 during a duel with political rival and Vice President Aaron Burr.

-

States Became Too Powerful And Numerous To Ever Amend The Problems

As it stands, the only method to change the electoral process on a national scale is through a constitutional amendment. Only one amendment has been made in the past to fix issues made obvious by specific events. The Twelfth Amendment was added to the Constitution in 1804 after a contentious presidential election in 1800. With the rise of political parties, the Federalist-controlled Congress had to select which of two Democratic-Republican candidates would be the respective president and vice president. The amendment, however, only changed specific rules that became apparent during that election.

Other problems have become apparent since the early 19th century, but there is little to no incentive to change. Some have argued that change is needed, but it takes two-thirds of both houses of Congress to first propose an amendment, and then three-quarters of the states are required to ratify it. Only then can an amendment to the Constitution be made. The current system, however, is beneficial for highly populated states, as they have greater say in electing the president. Furthermore, within the current two-party political system, the party that holds a majority in that state benefits from having the winner-take-all method.

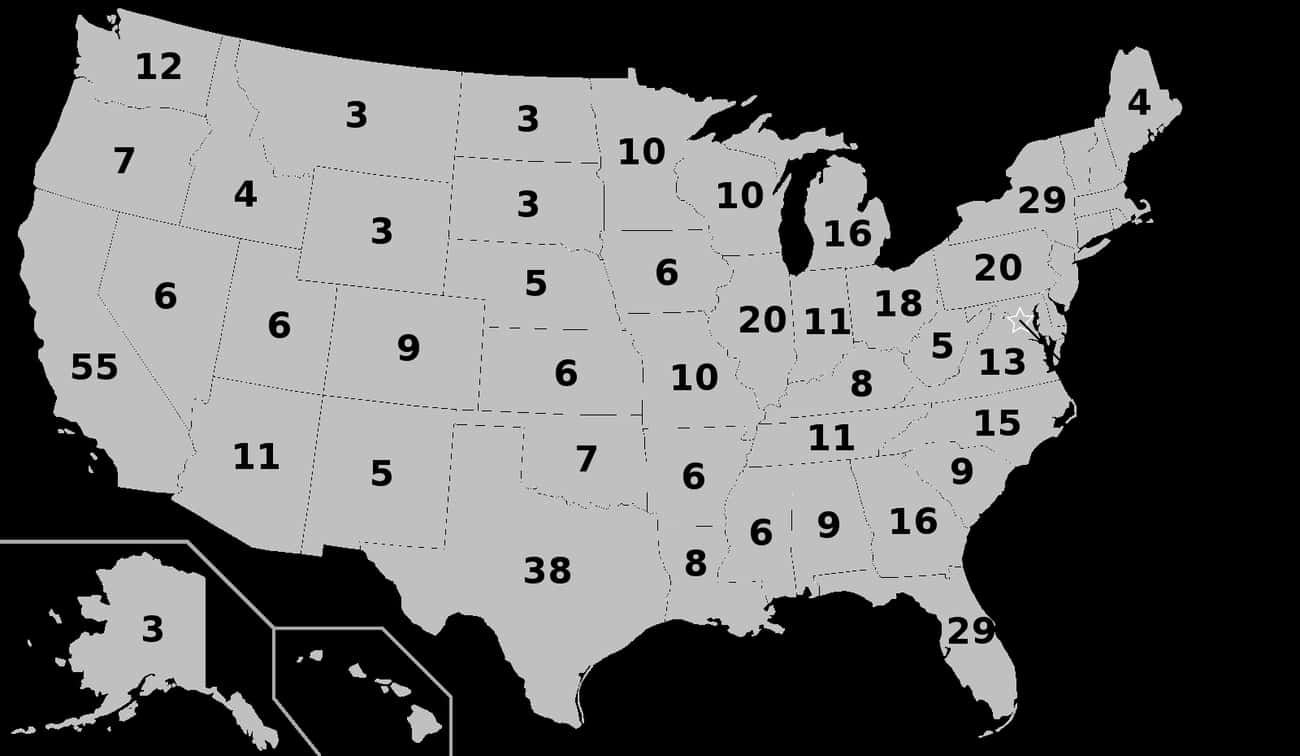

Take California for example. As of 2020, California is the most populous state in the entire country with almost 40 million people. The state holds 55 Electoral College votes, and has held as a Democratic stronghold since 1994. Statistics indicate that 46.3% of voters in the state are registered Democrats, while registered Republicans only make up about 24%. Furthermore, data from 2010 to 2020 indicates that about 40% of voters registered as independent or "no party preference" lean Democratic. In a state where Democrats have consistently held over 50% of the popular vote and majorities in both federal and state offices, there is no reason to give up the power to provide over one-fifth of the necessary electoral votes to the desired candidate. This is not a problem of a single party, however. The same held for the Republican Party when it held the majority in California between 1952 and 1988.

Conversely, a state like Alaska, with a population of just over 731,000 people, only has three electoral delegates. In comparison to California, the state has 1.8% of the total population, but a disproportionate 5.4% of electoral delegates. Any change where total population decides the president affects the power they may hold.

States Continue To Shape What The Electoral College Is

Despite every state having the ability to switch from the winner-take-all method to the congressional district method, the only two states that have are Maine and Nebraska. Both made changes relatively recently and neither state made that switch because they saw biases and problems with the former.

Rather, Maine adopted the congressional district method in 1972 as a result of the election of 1968 when there was a three-way race between President Richard Nixon, Democratic candidate Hubert Humphrey, and independent George Wallace. Officials had anxieties over providing all the electoral votes to a candidate who hadn't even received over 50% of the state's vote. Nebraska, on the other hand, wanted to get more attention from presidential candidates, so it split the electoral delegates with the hopes that maybe a single delegate could win the presidential election.

Source: Ocnus.net 2020

|

|