How they chose who and when to kill

We remember the Mongols as a force of pure violence, but beneath their bloodthirsty exterior lay military genius. They knew how to terrorize a region enough to prevent rebellion but still have something worth ruling over. But how much terror was enough? Were the Mongols actually far more peaceful than we imagine them to be?

Not really.

That’s it, right? The Mongols were every bit as violent as we think they were. You can’t conquer most of Asia without killing a lot of people.

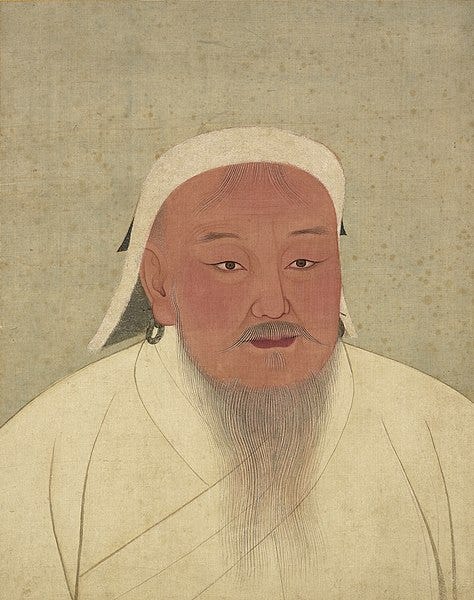

14th-century portrait of Genghis Khan. Original from National Palace Museum

Well, not quite. Although they were violent, they were controlled. Their greatest massacres always had a reason behind them, one which we see again and again.

The Mongols killed people who resisted. The greater the resistance, the greater the retribution. Cities that forced a long siege, or worse, killed a Mongol commander, would see their houses looted and citizens enslaved. Those who surrendered quickly would, for the most part, be spared.

This seems obvious, but it goes a long way towards understanding some of their most brutal campaigns. It is easy to assume that they were only out to kill, or that they did not care at all about the people they conquered. The latter is true to some degree, but even it fails to explain their actions.

The Mongols were pragmatic. Their objective was to conquer as fast as possible, and they didn’t care about human lives. For the most part, they didn’t set out with the intention of massacring a city. They wanted people to rule over, not ruins.

Frequently the desire for retribution, or for instilling terror, would become more important and lead to a slaughter. They understood exceptionally well the power of terror and took great pains to ensure that their reputation as merciless killers was known by everyone. They used the fear surrounding them to keep their vast empire in check and to make their expansion easier.

Ultimately their goal was conquest, and so they made sure that their massacres were controlled, to a degree. Artisans and craftsmen were often spared, as were towns that surrendered promptly. The vast killings they committed were as much a product of a high-level strategy as of a culture of violence within the armies.

It is easy to see their philosophy towards violence reflected in their campaigns. Their many, many conquests provide ample opportunities to see it play out, but the conquest of Khwarezm in 1219 provides a particularly clear example.

The invasion took place from 1219 to around 1221 under the direction of Genghis Khan and his sons. It was brutal even by Mongol standards, with the killings and mass exodus it sparked seeing some regions decline in population for generations. At the same time, there is a puzzling contrast between the cities that were chosen for destruction and those that were seemingly spared.

“… they do not seek territory or wealth, but only the destruction of the world that it may become a wasteland.” — Ibn al-Labbad

Some cities were looted and had their citizens enslaved and relocated, while others remained intact, and yet others were burned and rendered uninhabitable. Rather than simply being due to differences in command, the variations reveal how the Mongols responded differently to perceived acts of resistance.

The spark for the conflict was the execution of 500 Mongol merchant-ambassadors by the governor of Otrar, one of the largest trade cities in Khwarezm. The Shah of Khwarezm was justifiably worried that the merchants were also spies, and the nearness of several armies under Genghis’ sons exacerbated these fears. Whether the execution was on the Shah’s orders or not remains uncertain, but his actions afterward made it clear that he stood by it.

The deaths of the merchants provided Genghis with grounds for conquest, and so in 1219, he marched four armies into Khwarezm. The Shah had chosen to divide all his armies among the garrison, leaving none to fight the Mongols in the field. The Shah suspected the loyalty of many of his troops and feared they would desert or surrender in a battle.

This decision gave the Mongols a decisive advantage, but also lead to an increased number of massacres. Larger garrisons lead to longer sieges, which prompted retribution once the Mongols won.

The siege of Otrar illustrates the Mongol philosophy best: despite being the backdrop for the execution of the merchants, Genghis did not burn down the city and instead allowed the peasants and artisans to live. Though this seems like a small mercy, particularly since the peasants were relocated to distant parts of the empire, it makes it clear that the objective was conquest, not violence. Despite the city putting up five months of resistance, it was not enough to supersede the need for common laborers upon which the empire functioned.

On the other hand, the aftermath of the siege of Nishapur reveals what happens when they decided on retribution. During the siege, Togchar, one of Genghis’ son-in-laws, was killed and as vengeance, the city was exterminated. Toghcar’s widow leads the massacre, and when they concluded they heads were piled up in a grisly display. Nobody was spared, and reports claim that even the dogs and cats were killed.

The case of Nishapur makes it clear that the Mongols saw the death of a commander as a far greater insult than almost any other kind of resistance. When one of Genghis’ favorite grandsons was killed at the siege of Bamiyan the entire city was executed and it became forbidden to live there. It is a mercy for Khwarezm that there were only a few cases where commanders were killed, or else the already high death toll would have skyrocketed.

For the most part, the Mongols would spare artisans, even while the rest of the population was killed. At the siege of Gurganj, several hundred or thousand artisans were allowed to live, despite the city being destroyed so completely that it would be abandoned until a new one was built a decade later on Mongol orders.

The total extermination of a city was usually reserved for cases of rebellion, like at Balkh where the population was rounded up outside and executed. It was imperative to the Mongols that any rebellion be put down quickly lest it threatens to engulf their vast empire, and as a result cities which rebelled were utterly destroyed.

Although the “standard” procedure after a siege was to deport the artisans, loot the city, and then leave a governor ruling over those who remained, there are several cases in which a city surrendered early enough that the city was untouched. Herat was almost completely spared after it paid tribute and accepted a Mongol governor, while Balkh had suffered no pillaging up until it rebelled.

Whether or not a city would be spared largely depended on how important it was and whether or not it surrendered quickly. Major cities would invariably undergo looting even if they surrendered without a fight, simply because the Mongols wanted to make a point and extract resources.

Despite the existence of a rationale behind why some cities were decimated and others weren’t, there is no way to justify any part of what the Mongols carried out. They waged war without any regard for those they fought, and frequently without any regard for those they ruled over.

Even though their massacres were part of a larger strategy to terrify the enemy into surrendering without resistance, the reality remains that they killed hundreds of thousands across their Khwarezm campaign, and millions more over their century of terror. Genghis and his generals were mass-murderers, through and through. The world should be thankful that they only lasted as long as they did.