Ocnus.Net

Arab Society in Israel and the Elections to the 25th Knesset

By Ephraim Lavie, Mohammed S. Wattad, Aref Abu Gweder, Ilham Shahbari, Jony Essa,Meir Elran, INSS 20/11/22

Nov 20, 2022 - 12:26:21 PM

Despite the predictions of low voter turnout, a majority of the Arab public voted in the recent Knesset elections. An analysis of the voting patterns in the sector provides an interesting picture of the trends, drives, and demands of the Arab minority in Israel. Israel’s incoming government would do well to consider these points as it formulates policies that concern 20 percent of the overall population

Among other social barometers, the results of the November 1 elections to the 25th Knesset provide an insight on relations between Israel’s Jewish majority and Arab minority. Arab voter turnout was higher than expected, indicating an ongoing motivation of the majority of Arab citizens to integrate into the country’s fabric. At the same time, the rate of those who abstained from voting or voted for the nationalist Balad party in higher numbers than before also suggest a sense of apathy toward the Israeli political system and a growing inclination toward nationalism and segregation. Overall, the Arab voting pattern did not change from the recent past. However, the expected composition of the 37th government, and particularly the strong position of Religious Zionism, which is perceived as hostile to Arab society, could delay or even change the government’s policy, which since 2015 has made significant investments in the promotion and integration of Arab society. Marginalization could darken the public mood further and encourage extremist nationalist elements in both camps, perhaps even leading to widespread violent clashes that could challenge the nation’s law enforcement agencies. Against this background, the government should continue the previous policy, initiated by Benjamin Netanyahu, of developing Arab society and reducing violence and crime within it. This would help secure Israel’s long-term interest and the social resilience of all sectors of its population.

For the Arab public in Israel, most of whom in recent years expected their elected representatives to focus on essential civil matters and participate in the government coalition, the results of the November 1 elections mark a challenging shift, particularly given the fragility and fluctuations in the sensitive relations between Arabs and Jews, which reached a grim climax in the violent clashes of May 2021.

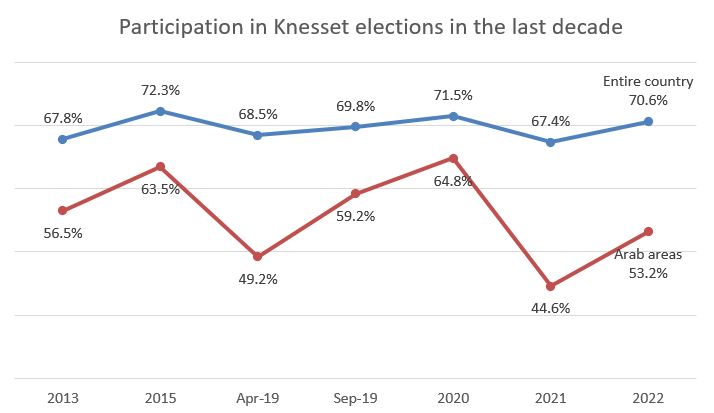

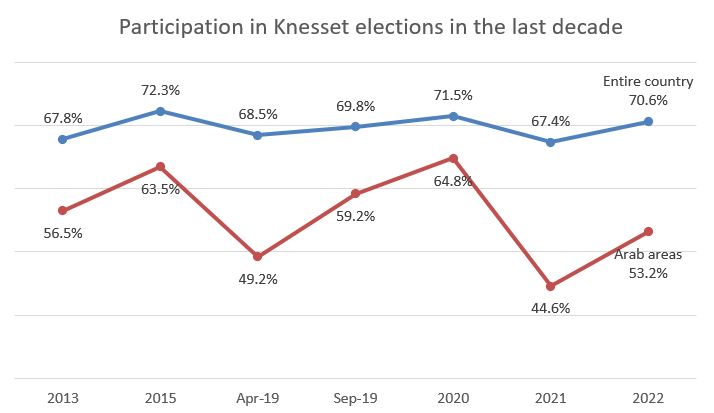

Results of Voting in Arab Areas

Voter turnout for the 25th Knesset in the Arab sector was 53.2 percent (10 mandates), an increase over the low point recorded for the 24th Knesset elections in March 2021 – 44.6 percent. The results differed from most pre-elections predictions of a considerable further decline in Arab voter turnout. Still, turnout this time was lower than in the 2020 elections to the 23rd Knesset, which reached a peak of 64.8 percent. Then, the full Joint List (comprising Hadash, Ta’al, Balad, Ra'am) achieved a record 15 mandates.

Results: 85.8 percent of the Arab voters voted for Arab parties, with the following distribution:

35.2 percent voted for Ra'am, which received 194,047 votes, earning 5 mandates. Consequently, for the first time, Ra'am became the largest party in the Arab sector.

28.8 percent voted for Hadash-Ta’al, which received 178,735 votes and 5 mandates.

21.8 percent voted for Balad, which received 138,617 votes but did not pass the threshold for a mandate.

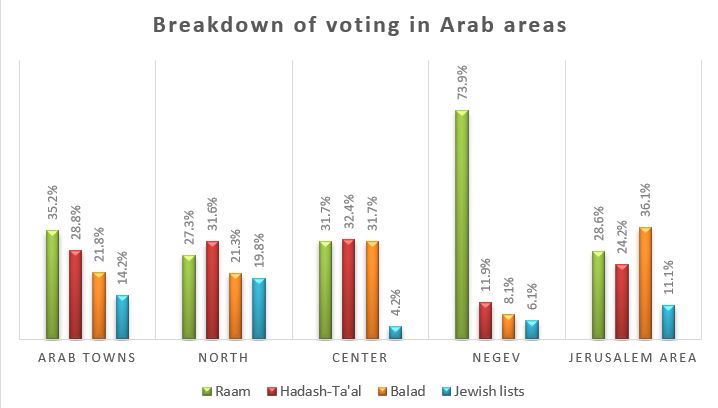

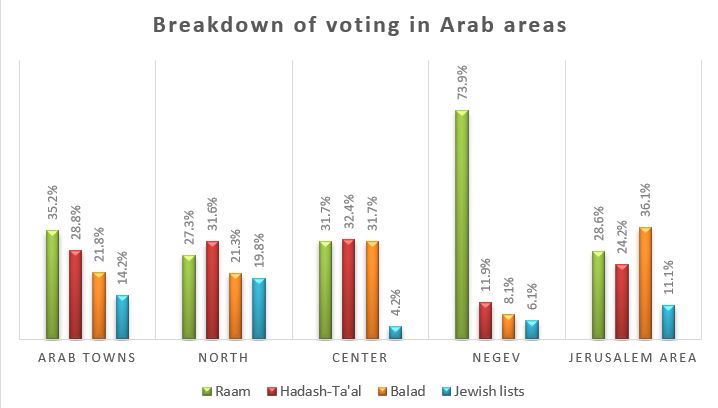

Breakdown by region:

In the north – Galilee, the Valleys, Carmel, and Nof Hacarmel – voters tended to favor Hadash-Ta’al.

In the center – "the Triangle" – votes were closely split among the three parties.

In the south – the Bedouin towns in the Negev – Ra’am received about 75 percent of the votes.

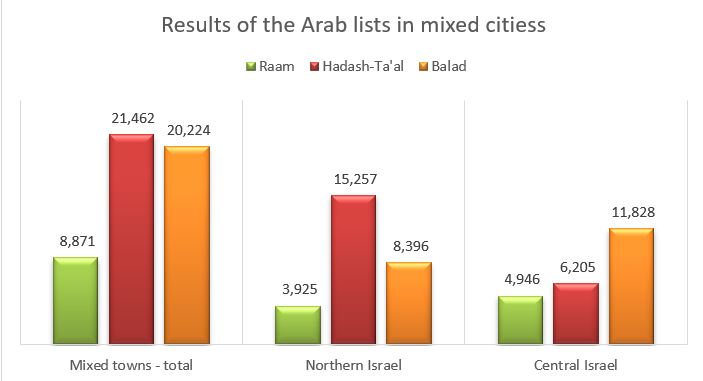

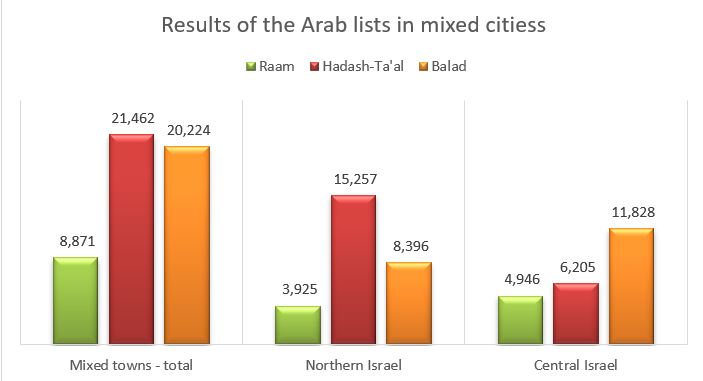

Voting in cities and towns with mixed Arab and Jewish populations resembled the general urban voting rate and was almost the same as the rate when the Joint List reached its record strength back in 2020. In the seven mixed cities there was close competition between Hadash-Ta’al and Balad: in Ramle, Lod, and Jaffa voters leaned toward Balad, while in the north – in Haifa, Acre, Nof Hagalil, Ma’alot-Tarshiha – the voters favored Hadash-Ta’al; the pragmatic Ra'am lagged far behind. The relatively high rate of voting for the nationalist Balad party represents a new phenomenon compared to the traditional dominance of Hadash in the mixed cities.

Votes by Arabs for Jewish parties declined considerably, reaching only 14.2 percent of the vote. This has been an ongoing trend since the 1990s, now bolstered further by the absence of Arab candidates in realistic positions on the Jewish parties’ lists. Most prominent here were the National Unity Party with about 14,000 votes, Meretz with about 13,000, and the Likud and Yisrael Beiteinu, with about 10,000 votes each.

In the Bedouin localities in the Negev, voter participation was relatively high: in the established townships, including Rahat – about 60 percent; in the regional councils – about 57 percent, and in the unrecognized villages, unsurprisingly, less than 40 percent. The big winner here was Ra'am, which received about 75 percent of the votes, even though there was only one Bedouin candidate from the Negev on its list in a realistic position (Walid Khalil al-Huashla). Hadash-Ta’al, with two Bedouin candidates in high positions, only received about 8 percent of the Bedouin votes, similar to Balad.

The Political Mood in Arab society

The most striking trend within the Arab public seems to be the sense of apathy and of “no change.” Many claim that the experience with the outgoing Bennett-Lapid government was no better than with the Netanyahu governments. Nonetheless, there is concern with the results, particularly the gains of the Religious Zionist Party, coupled with the concern that Itamar Ben Gvir and Betzalel Smotrich will be part of the government. On the other hand, there are those who suggest that in many ways right-wing governments have a pragmatic attitude toward the Arab public, and point out that nationalist rhetoric notwithstanding, the five-year plans were launched by right-wing governments.

It appears that the heterogenous Arab public is divided, confused, and frustrated by the dismantling of the Joint List and the major gains scored by the Religious Zionists. Still, there are those in Arab society who see the internal split as an opportunity to enrich the political discourse in the Arab sector, particularly among the leading parties:

Ra'am, a party with a religious and nationalist identity, which accepts the Jewish identity of the State of Israel and seeks to achieve full civil and economic equality for its Arab citizens.

Hadash, a nationalist-civilian party, which promotes the idea of “a state for all its citizens,” demands collective nationalist rights for the Arabs, and highlights their status as an indigenous minority.

Balad, a clearly nationalist party that also supports the idea of “a state for all its citizens” and demands expression for this idea in the state’s institutions and laws.

Ta’al, a more pragmatic social-nationalist party promoting the idea of “a state for all its citizens” as well and calls for making Israel into a binational state, Jewish and Arab.

Almost half the Arab public did not participate in the elections; some because of apathy, and others because of opposition in principle to voting for the Knesset, which in itself expresses recognition of the state institutions and the benefits of political participation as a lever for integration. This isolationist approach is now likely to grow stronger, particularly if faced with a more exclusionist approach by the government.

Significance of the Arab Voting

There are two main reasons for the relatively high voter turnout among the Arab public in 2022: first, the desire of many Arab citizens to continue their integration and influence in the state’s decision making processes; and second, the relatively broad support for the nationalist Balad party and the desire to help it pass the electoral threshold.

The increased strength of Ra'am (from four to five mandates) and its emergence as the leading Arab party prove that a large segment of the Arab population supported its pragmatic approach and participation in the coalition. Most of the votes for Ra'am came from the Bedouin population, while the party was unable to significantly expand its support in the center and north of the country.

The support for Hadash-Ta’al also symbolizes a pragmatic approach, while retaining the national identity. However, Hadash is weakened, and without Ta’al it would not have passed the electoral threshold. Balad, with its extremist nationalist approach, while failing to pass the threshold, did manage to increase the number of its supporters. This important trend reflects a rise in the numbers of those who are uneasy with active political integration.

The formation of a right wing government, in which the extreme right will have considerable levers of political pressure, might have a negative effect on the incoming government’s approach to the Arab minority. This might be the case not just at the level of alienating rhetoric, which is likely to darken the public climate between Jews and Arabs, but perhaps also at practical levels, impacting the full implementation of the five-year plans to enhance the socio-economic situation of Arab citizens. Particularly important is the plan to reduce violence and crime in Arab society, which is vital for Arabs and Jews alike. Interference with these plans would clearly jeopardize the national Israeli interest.

Under such circumstance there is concern that relations between Jews and Arabs will deteriorate, especially if and when volatile situations of friction arise, mainly in Jerusalem and the holy sites, which could spill over into the mixed towns and the Negev. This would be particularly likely in the event of increased violence with the Palestinians, particularly religious clashes in East Jerusalem. Mutual violence could erupt and reinforce extremist elements in both camps. These would require a tough and effective law-enforcement response, for which the Israel Police is insufficiently prepared.

Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

The composition of the 37th government is likely to cause a restrictive or even exclusionist approach compared to previous governments, including those headed by Netanyahu. This would contradict the concept, which was previously recognized by both centrist and right-wing governments, that the development and integration of Arabs in the social, economic, and political fabric of the state constitute an interest of supreme national importance for Israel’s social, economic, and moral resilience.

Most Arabs in Israel are interested in integration. They do not see it as contradicting their Palestinian national identity. Indeed, Jews and Arabs maintain practical interactions in many spheres and their routine conduct is mostly guided by the notion of shared interests. The trend toward integration is also the basis for cooperation between Arab leaders and state institutions.

Against this background, the government should avoid alienating, inciting, and voicing racist rhetoric that amounts to questioning the loyalty of Arab citizens. The government should adopt a policy that continues to encourage integration of the Arab public as equal partners. In the long run, this policy will help improve relations between Arabs and Jews and the state, while weakening or restraining extremist processes and groups. This long-term policy will best serve Israel’s national interest.

It is therefore vital to continue with the implementation of the five-year plans for development and progress in Arab society and the struggle against violence and crime, including the plans for the Bedouin society in the Negev.

Source: Ocnus.net 2022