|

Ocnus.Net International Due to tensions with Ukraine and the West, Russia is seeking to shift towards Asia and to expand its influence in the post-Soviet space. Indeed, he contends that Moscow wants to reposition itself as a central Eurasian great power. To further this goal, and accrue additional international leverage, Russia has led the way in creating the Eurasian Economic Union, a surprisingly robust multilateral organization that is reshaping the regional geopolitical and economic landscape. Perović suggests that Eurasia is changing and it’s time for Europe to pay attention.

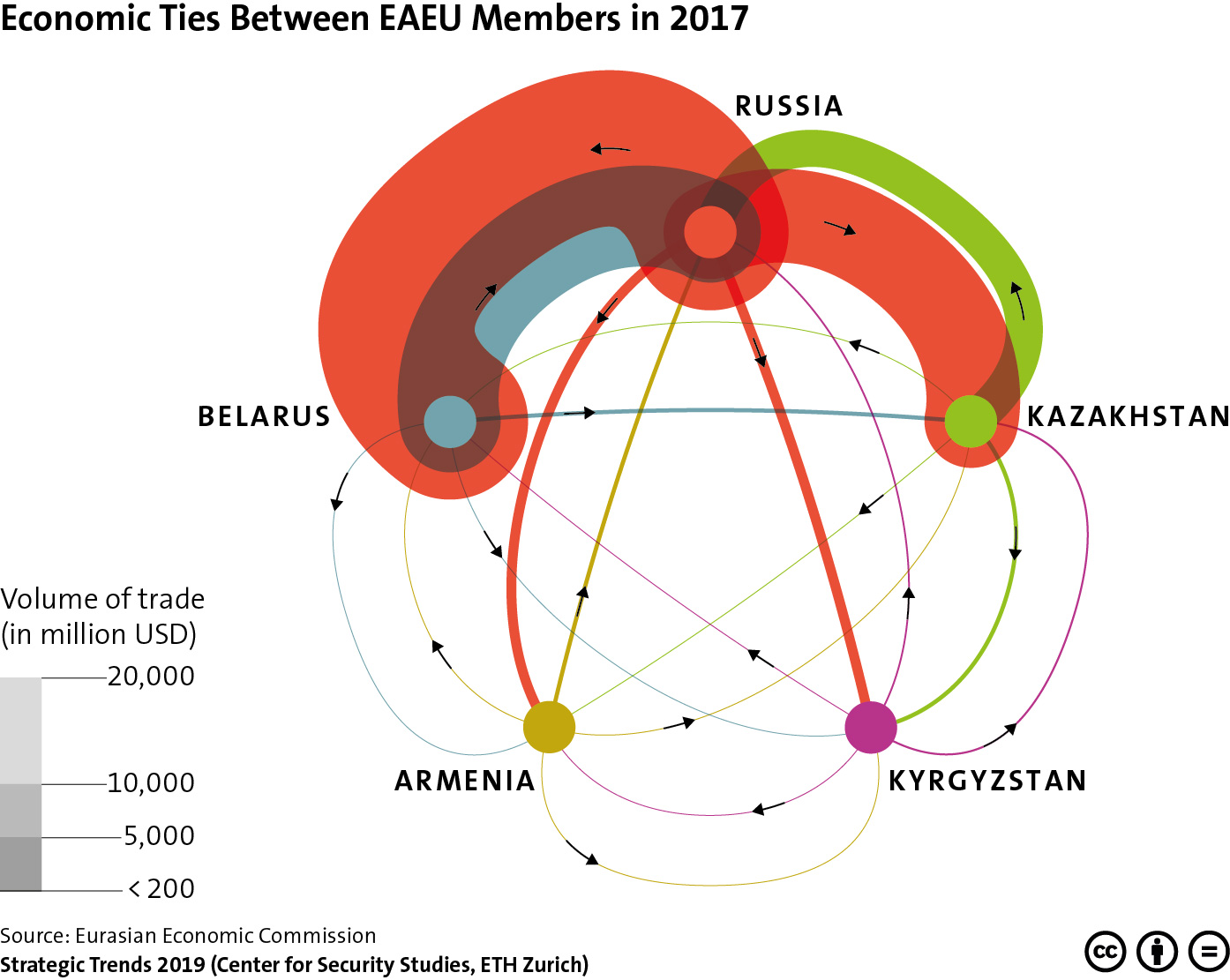

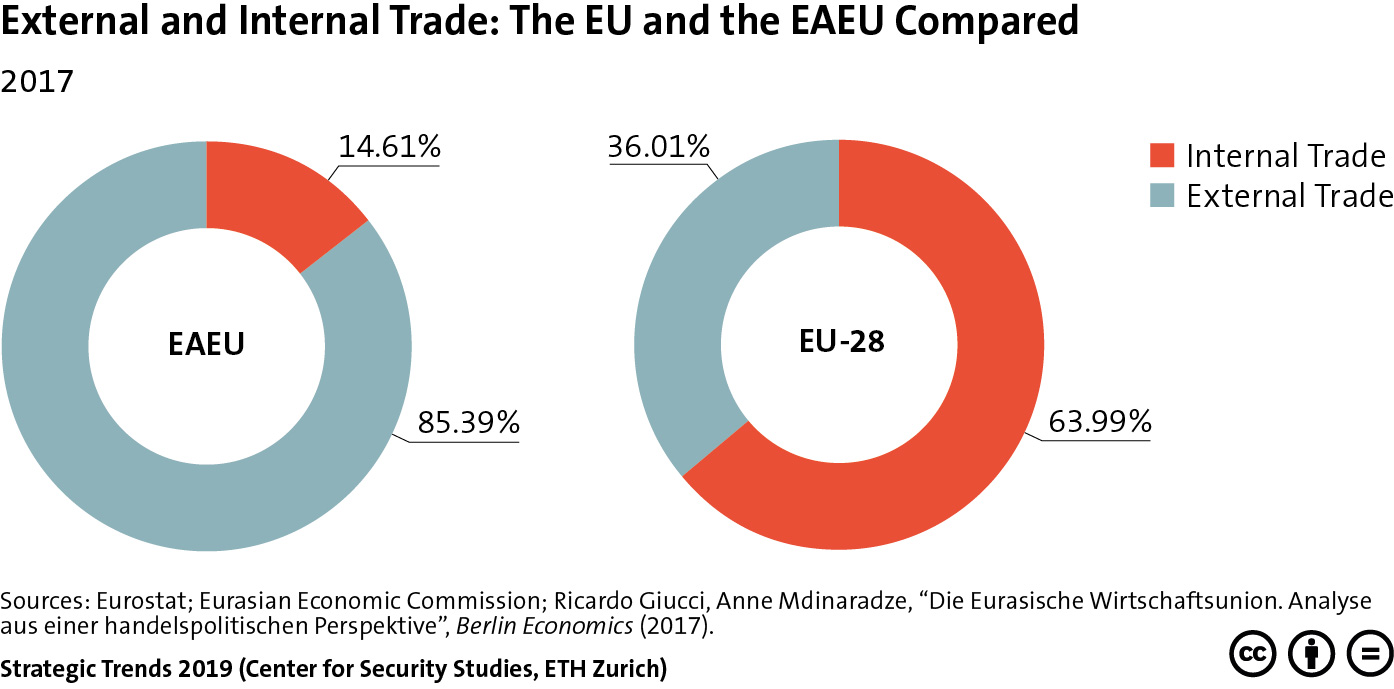

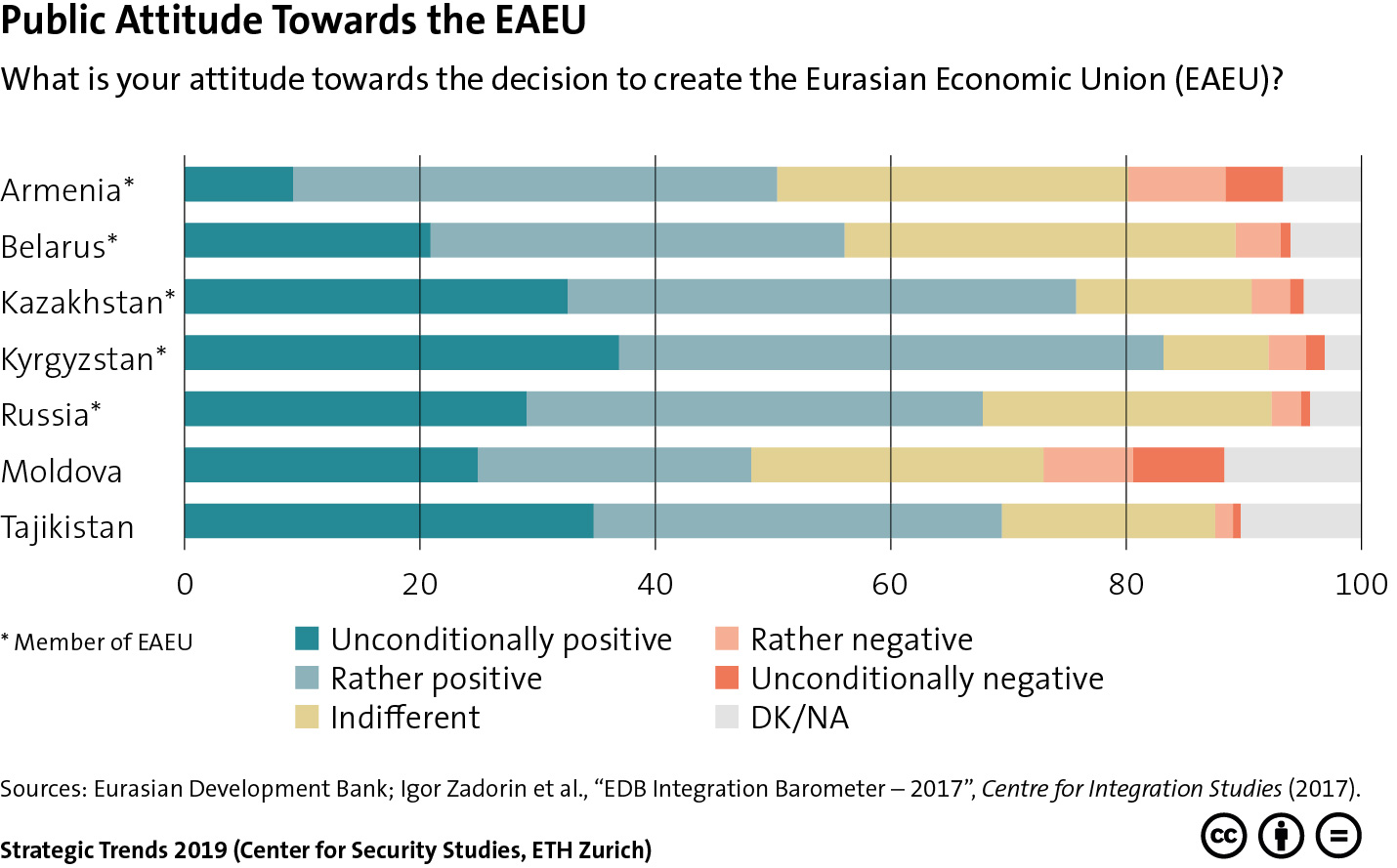

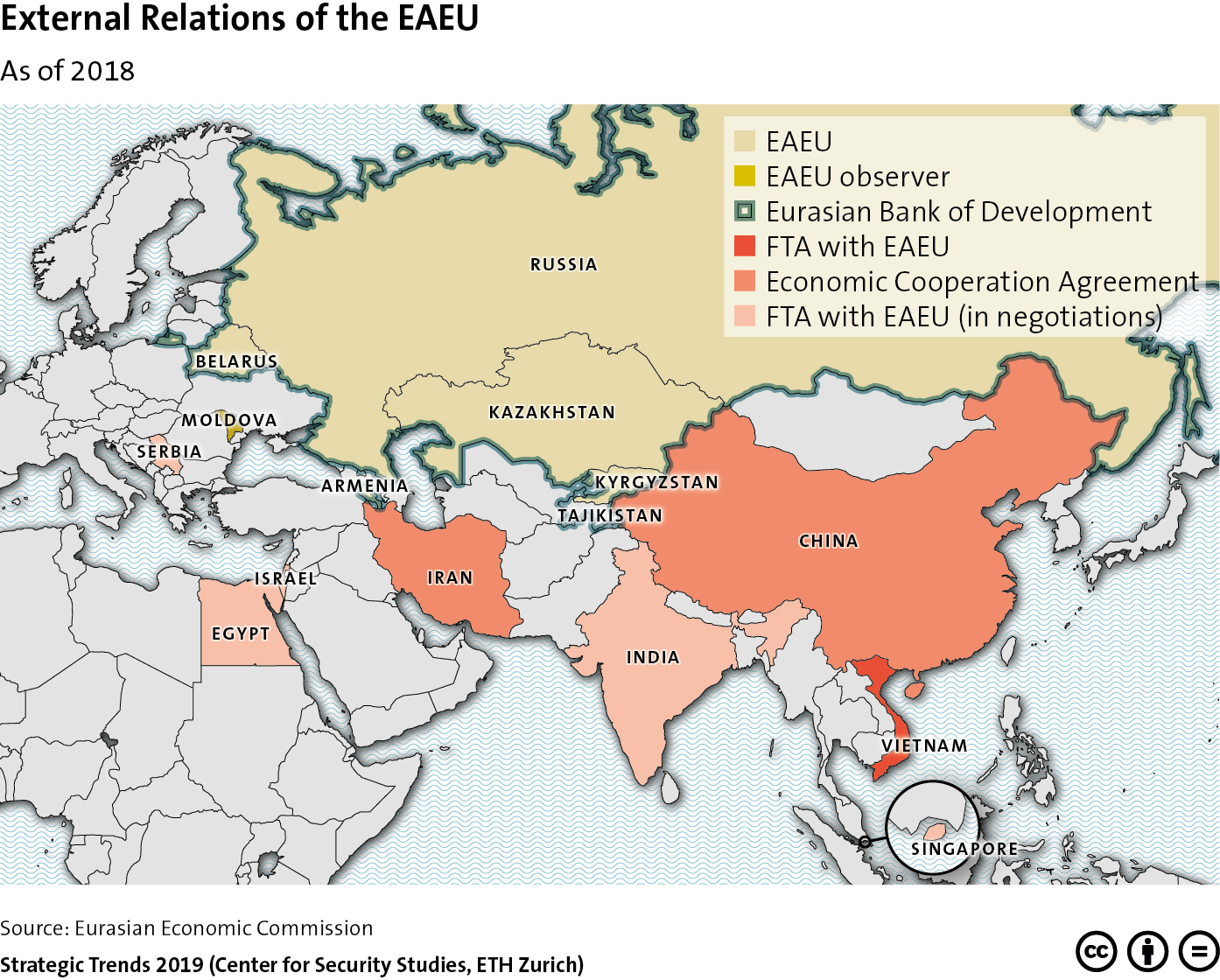

In light of its rift with Ukraine and tensions with the West, Moscow is seeking a more influential role in the post-Soviet space and is reorienting its policy towards Asia. Rather than breaking with the West, Russia wants to reposition itself as a central Eurasian great power. In order to gain influence in “Greater Eurasia” and accrue additional international leverage, Russia has led the way in creating the Eurasian Economic Union, a surprisingly robust multilateral organization that is reshaping the regional geopolitical and economic landscape. Eurasia is changing. It is time for Europe to pay attention. It would be misleading to see Russian integration efforts simply as an attempt at restoring the old Soviet Union. While the EAEU has turned into the most successful regional integration project since the Soviet Union’s break-up in 1991, Moscow’s ultimate goal is not so much to reconstruct a strong supranational state, like the Soviet Union, but to maintain as much control as possible over developments in its post-Soviet vicinity. Facing challenges from an expanding European Union in the west, and China’s rise in the east, Moscow aims to use multilateral organizations like the EAEU as yet another tool in its efforts to strengthen Russia’s position in an ever more competitive international environment. Russia wants to perform the role of Eurasia’s doorkeeper, making sure the states of the region remain within its sphere of influence and preventing them from joining Western institutions. At the same time, through regional alliances, Moscow seeks to boost its standing in world affairs, hoping to increase its leverage when engaging with other powerful states and organizations. Russia’s position in post-Soviet Eurasia is still uncertain, and remains contingent upon the interests of the states of the region, as well the behavior of outside powers. Even though some of Russia’s post-Soviet neighbors are now tied closely within the framework of the EAEU and other regional organizations, they are nevertheless unwilling to give up their political sovereignty, and also want to see a tangible profit from their association with Russia. The Kremlin understands that coercion might backfire, and that it needs to make sure the Russian-dominated EAEU is successful and attractive to all of its members, and not seen as serving Russian interests only. While Russia will not allow any member to leave the union, the bargaining power of states associated with Russia is not necessarily weak. Also, while Russia still is the most important actor within the post-Soviet space, Moscow faces competition in the region as other states, and especially China, have been making increasing inroads. Through regional organizations such as the EAEU, Russia hopes to contain Chinese influence, especially in Central Asia, and develop a more coordinated approach towards China and other powers engaged in the region. This chapter looks into the nature of current integration processes in the post-Soviet space. Though Russia cannot and will not abandon Europe any time soon, the shift towards Asia, and Moscow’s efforts to strengthen ties with its neighbors, will ultimately have consequences for Russia’s international standing and relations with the West and Asia. While European-Russian economic relations have suffered due to political tensions, trade between the EAEU and Asia has increased significantly. Also, with the US engaged in a trade war with China, economic cooperation and trade in the larger Eurasian and Asia-Pacific region is likely to continue to expand. It is time that Europe, which has so far rejected entering into a dialogue with the EAEU, reconsidered its policy. Otherwise, Europe might be passing up economic opportunities, and Russia and the whole of Eurasia will continue to drift eastward. Russia and the Post-Soviet Space Russia has always considered the post-Soviet space to be a zone of vital interest. While officially recognizing the former Soviet states’ independence, Moscow has accepted its neighbors’ sovereignty only insofar as their policies are not seen as detrimental to Russian national interests and its claim of regional predominance. As a putative great power, Russia sees this claim legitimated by common history and culture, ethnic, economic and political ties, as well as larger security considerations. During most of the 1990s and well into the 2000s, Russia did not pursue an active integrationist policy. If Russia was economically weak, its neighbors were still weaker, and Moscow was able to maintain its hegemonic position and dictate the terms of relationships. Russia felt comfortable with the situation as it was and saw no need to push for re-integration. Moreover, Russia’s focus was rapprochement with the West and the broadening of trade and economic ties with Europe. It was from early 2000s onwards that Russia set out on a more proactive policy towards the states in its immediate neighborhood. This was connected with three major developments: First, under Vladimir Putin’s presidency, Russia became politically and economically much more stable than during the Yeltsin years, and due to higher incomes from the sale of oil and gas abroad, the Russian state had also more resources at its disposal to support an active foreign policy. Second, while Russia was stabilizing under Putin’s increasingly authoritarian leadership, the Kremlin saw itself confronted with democratic upheavals and regime change in its near abroad. The revolutions in Georgia in 2003, in Ukraine 2004 and (to some extent) in Kyrgyzstan in 2005 brought new elite groups to power, which were reform-minded and sought cooperation with the West. Third, and most importantly, Western states and organizations made inroads into the post-Soviet space. The Baltic states became members of North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 2004, and both the European Union and NATO concluded partnership agreements with a number of other post-Soviet states. At the same time, China became more engaged economically, especially in Central Asia. Russia lost some of its leverage in the sphere of energy transportation, as a number of pipelines were built circumventing Russian territory with the help of foreign companies. While gas and oil from Azerbaijan is now reaching Western markets via Georgia and Turkey, oil and gas pipelines connect Central Asia directly with China. Towards Multilateral Integration As Russia saw the post-Soviet zone slipping from its grasp, the Kremlin reacted: In 2002, under Moscow’s lead, six former Soviet republics, Russia, Armenia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Belarus, decided to transform the Collective Security Treaty (established in 1992) into a military alliance, the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO). While this organization has not yet turned into an effective, fully fledged security alliance like NATO, the individual members have committed themselves to working together more closely, they are regularly holding common military exercises and, most importantly, Russia or any other CSTO member has the right to veto the establishment of new foreign military bases in CSTO-member states. Also, in 2007 the organization concluded an agreement with another major security organization, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), which has developed into an important forum for dialogue among all the main powers of the Asia-Pacific region on security, political, and economic issues.2 The empowering of existing regional organization such as the CSTO and the conclusion of agreements with other regional organizations indicated the new course of Russian foreign policy at the time: Moscow wished to strengthen those regional organizations it was able to dominate and sought to build up relations with other states and organizations. As in the field of security, various economic groupings with shifting numbers of countries were created during the 1990s, but these organizations were not very effective. Beginning in the early 2000s, Russia began to counter the influence of outside powers by strengthening its economic position with the help of some of Russia’s large state-controlled energy companies, including Gazprom, Lukoil and RAO UES.3 It was only in 2008 – 2009, however, that Moscow intensified its integration efforts in a multilateral framework.  Based on the Eurasian Economic Community organized in 2000 by Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, integration was intensified with the launch of a custom’s union in 2010, joined also by Armenia (but not Tajikistan). In 2011, eight members of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Ukraine, Moldavia, Armenia, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, agreed on the formation of a free trade area. A year later, Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan deepened economic integration by organizing the Common Economic Space. On May 29, 2014, the presidents of the three states signed a treaty establishing the EAEU, and on January 1, 2015, when the agreement came into force, Armenia and (in August 2015) Kyrgyzstan joined the organization.4 From Greater Europe to Greater Eurasia For most Russian foreign policy specialists, the idea of Eurasia remained marginal until it was reinvigorated by Vladimir Putin during his tenure as Russian prime minister. In an article published in Izvestiia in October 2011, Putin provided the idea of Eurasia with a new conceptual framework.5 Rejecting the notion that the formation of a new union among post-Soviet states was to be seen as a “revival of the Soviet Union,” he suggested that a “powerful supranational association” was capable of becoming “one of the poles in the modern world.” Trying to diffuse the notion that a future Eurasian Union might be seen as an attempt to “cut ourselves off” or to “stand in opposition to anyone,” Putin presented this project as part of a future “Greater Europe” stretching from “Lisbon to Vladivostok.” Essentially, what Putin proposed was the establishment of a free trade area between the European Union and the emerging Russian-dominated Eurasian bloc. This idea, however, received a blow in the aftermath of the Ukraine crisis and the ousting of president Viktor Yanukovich in February 2014, when it became clear that the new Ukrainian leadership hoped to establish closer relations with Europe. Sanctioned and isolated by the West in retaliation for the annexation of Crimea and military support for pro-Russian forces in eastern Ukraine, Moscow needed to adjust its Eurasian strategy. The Kremlin intensified efforts to strengthen its influence in the post-Soviet space, and gave more weight to the Asian vector in its foreign and economic policy. Russia’s turn to the East started before the Ukraine crisis and as a result of China’s economic rise. But the Ukraine crisis accelerated Moscow’s geopolitical reorientation. In a symbolic move and in order to underline Asia’s new importance, in May 2014 Moscow and Beijing signed a 30-year deal worth 400 billion USD to deliver gas from Russia to China via a new pipeline, finalizing an agreement that had been negotiated on and off for nearly twenty years.6 In line with Russia’s domestic discourse regarding the right to a follow its own, “sovereign” path to democracy, the alignment with China dovetailed with the country’s quest for a “sovereign” path in its foreign policy. As highlighted in a report by a group of leading Russian foreign policy experts, strengthening cooperation with China seemed not only politically and economically advantageous, but also marked a “moral” turn, as both countries were seeking “to promote a non-Western pattern of global development”, striving to protect their “national sovereignty” and increasing “their influence.”7 Russia was not closing its doors to Europe, but “the Great Eurasian” project was now also open to China, as Putin declared during the 2016 Petersburg Economic Forum.8 This rhetorical shift highlighted the fact that Asia had gained in economic importance for Russia. However, the Kremlin knew it could not afford to break with Europe; this would have been economically damaging and clashed with the country’s cultural identity. Also, while Asia has become more important to Moscow as an economic partner, Russia is still only a minor factor for most Asian countries. There is still a mismatch between the declared political goals of closer Chinese-Russian relations and actual Chinese investment, especially when it comes to Russia’s underdeveloped Far Eastern territories, which border China and are in need of investment. Moreover, while Russia is part of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative, which aims to build up infrastructure in order to link China with Europe and other global markets, it is not central to the undertaking, as most of the projects are in Central Asian states and Kazakhstan in particular. Russia’s shift to Asia acknowledges new geo-economic realities, but should also be seen as a narrative strategy and function of its policy towards Europe: Given the tensions with the West and the fact that Brussels is not interested in a dialogue with Moscow or the EAEU, a plausible way to get back to Europe is through Asia and through the strengthening of its position in the post-Soviet Eurasian space. Many in Russia believe that, by forming coalitions with other powerful states, Moscow will have more leverage in dealing with Brussels.9 Russia’s turn to the East is, in part, an attempt to gain international leverage and eventually form a more equal relationship with Europe. Potential and Limits of Eurasian Integration From Moscow’s point of view, building Greater Eurasia means that Russia remains at the center of everything that is going on in its immediate neighborhood, or what Russian officials call the larger “Russian World” (Russkii mir). If Russia’s goal is to prevent its neighbors from independently forming trade and political connections, Moscow will need to maintain control over regional developments. Russia has therefore been striving to deepen mutual interdependencies and to tie its neighbors together in an increasingly dense network of military, security, political, and economic relations. The EAEU is not the only, but currently the most important tool for fostering closer regional alliances and ensuring continued Russian dominance. The prevailing view among Western observers is that the EAEU is not an effective regional organization comparable to the European Union, but rather a Russian-controlled group of states which would rather align with Brussels, if they were given the possibility. Accordingly, there is skepticism that the EAEU will turn into an effective multilateral organization, as none of the members, including Russia, seem willing to cede substantial power to a supranational body.10 Others doubt that an organization dominated by authoritarian states will achieve much in terms of integration, as the removal of internal barriers on trade and the movement of goods, people, and services usually demands a certain openness, the application of the rule of law, and economic liberalization, none of which is in the interest of authoritarian rulers.11 Some point out that in authoritarian states, loyalties tend to be with the respective national political leaderships, and in case of disagreements, EAEU bureaucrats might prefer not to take risks and to stick with decisions taken by their respective governments.12 Even though it is likely the EAEU will face obstacles as it develops further, no other multilateral organization created in the post-Soviet space has achieved a higher degree of integration. The EAEU treaty is a technical document with no overarching ideology or specific values inscribed. The signatories pledge to deepen economic integration and remove barriers to the free movement of goods, services, capital and workforce; they also agree on the specifics of the decision-making process and the set-up of an institutional architecture, which is largely modeled on the European Union. While the most important decisions are taken by the Supreme Eurasian Economic Council, which is comprised of the heads of its member states, the daily work is carried out by the Eurasian Economic Commission (EEC), which is a permanent body based in Moscow, and consists of two representatives of each member state. Other important governing bodies of the EAEU include the Interstate Council, at the level of heads of governments, and the EAEU Court of Justice, which is based in Minsk.13 As with all multilateral organizations, removing internal barriers on trade and the movement of goods, services and people infringes upon national sovereignty. The fact that the EAEU has achieved harmonization of external customs tariffs means that decision-making about tariff issues has now been effectively transferred from the national states to the union level. The EAEU has also managed to abolish, at least to a large degree, internal customs borders and has reduced internal constraints on labor mobility and capital movement. Even though the EAEU’s existence has been marked by petty trade wars, economic crises, and disputes over trading rules, there has been progress as well: For example, the EAEU recently succeeded in creating a common market for the free circulation of pharmaceutical products, after agreements were reached on common standards regarding registration, production, and handling of medicine.  Especially ambitious is the EAEU’s plan to create a common energy market. By 2019, the union envisions a common electricity market, and, by 2025, a common market for oil and gas. If realized, this would give EAEU operators unrestricted and equal access to energy networks in other EAEU countries. Also by 2025, the EAEU plans to eliminate all obstacles and limitations to transport via road, rail and water. For the purpose of creating a unified transport zone and a common internal market for transport services, the EAEU aims to create a uniform electronic transport control system. The member states have also agreed to establish a common supranational body on financial market regulation by 2025 in order to ensure the regulation of a future unified financial markets. Given the amount of work already done, as well as the institutional structure put in place, it seems unlikely that the EAEU will falter any time soon. The bureaucratic apparatus of the EEC has grown to over 2000 employees; this body, which is currently chaired by former Armenian prime minister Tigran Sargsyan, is taking over responsibility of an increasing amount of laws.14 Therefore, the more realistic scenario is that the EAEU will increase its degree of integration, achieve further positive economic results, and continue to forge trade agreements with other states and organizations. In fact, after the difficult initial years, the economy within the EAEU-zone is showing signs of recovery. Further positive news will make the project more attractive, not only to current members, but to third parties as well. For example, Uzbekistan, although not a formal EAEU member, is currently harmonizing its import tariffs with EAEU norms. In 2017, Moldova became the first state to be granted official observer status to the EAEU. In the meanwhile, over a dozen states and several international organizations have concluded cooperation agreements with the EAEU. The Russian Challenge The challenge with this type of integration is that the EAEU is not so much about joining together in a community of equals, but about individual states associating themselves with Russia. In the EAEU, Russia is accounting for some 87 percent of the union’s total GDP, and makes up for some 80 percent of the EAEU’s population.15 Russia’s annual military budget exceeds the combined spending of all the other EAEU members by a factor of twenty. Because of these massive regional asymmetries, the cost of a member state dissociating itself from Russia could be very high. As the Ukrainian case has demonstrated: leaving or staying is potentially a matter of war and peace, and it seems that the individual EAEU members are well aware of this. Having learned from the Ukraine experience, leaving the union was never on the agenda of the new leaders who came to power after Armenia’s “velvet revolution” in spring 2018. The member countries are thus very careful in dealing with Russia, and are mindful of the Kremlin’s sensitivities. But since they know how important this union-project is to Russia politically, they also have a fairly large maneuvering room, and their negotiating position via-a-vis Moscow is not necessarily weak. For example, every time Russia’s closest ally, Belarus (which is united with Russia in the framework of the Russia-Belarus Union State created in 1997), does not get from Russia what it wants, it threatens to boycott integration projects and Russia, which is not interested in yet another conflict, usually tries to accommodate Belarussian interests, for example by lowering energy prices or by writing off debts. Notwithstanding membership in the EAEU, both Kazakhstan and Armenia have concluded an Agreement on Comprehensive and Enhanced Partnership (CEPA) with the European Union, which is in fact a “light” version of the EU Association Agreement with the prominent exception of sections on trade policy, which are now in the competence of the EAEU. Kazakhstan also continues to negotiate deals with China, and has been one of the key drivers behind the idea to reactivate the establishment of a union among all the five post-Soviet Central Asian states. But Russia too, at times puts its economic interests above those of the union. When the other members of the union declined to follow Russia imposing punitive measures in response to EU economic sanctions against Russia for its aggressive actions in Ukraine in 2014, or did not support sanctions imposed by Russia on Turkey in 2015, Russia ignored this and went ahead imposing its own sanctions on Western (and later Turkish) goods. If Russia sees its interests at risk, it tends to disregard the restrictions a common regime would usually impose. At the same time, however, Russia also understands that especially since the Ukraine crisis, its neighbors react more sensitive to any form of real or perceived political and economic pressure. Although it is clear that Russia, as the most powerful of all the members, has the largest amount of influence over the decision making process within the union, the key decisions are reached in consensus among all heads of states and it would be wrong to assume that Russia can simply ignore the interests of others. In fact, by promoting the EAEU as an institution which serves to protect the interests of all of its participants, Moscow is well aware that coercion as a means to keep the union together is likely to backfire, and therefore tries to alleviate these countries’ fears of Russian dominance. While Russia wants to avoid that integration becomes a burden to its own economy, it also needs to make sure the union is successful and not seen primarily as a Russian dominated project, obliging Russian goals only. The Rationale to Join the Union Even though Putin has been stressing the economic advantages of deeper integration among former Soviet republics, it seems quite clear that Moscow’s primary interest was never so much in the economic side of the project (after all, the current union accounts for only about 6 percent of Russia’s overall trade), but the larger geopolitical and geo-economic gains. Following the logic that “great powers do not dissolve in some other integration projects but forge their own,”16 Russia has been seeking to establish the union as an important international actor and economic heavyweight in order to raise its own standing in world affairs. In fact, given Russia’s importance to all of the member states, most of the trade and other economic issues could be dealt with bilaterally between Russia and the individual states of the region. This is especially true for Belarus, whose trade is almost exclusively with Russia, but not with other EAEU members. The overall level of internal trade among the member states is still relatively low, accounting for only 14.6 percent of total trade in 2017 (for comparison: in the EU, around 64 percent of trade was between members of the union in 2017).17  Even though the external trade of most individual members is much higher than internal trade (in the case of Russia and Kazakhstan, this is due to the fact that these countries export most of their oil and gas outside the EAEU-area), there still is a certain logic in fostering closer cooperation, namely due to strong legacies from the past, which manifest themselves not only in integrated rail and road transportation networks, energy connections and common technical standards originating from Soviet times, but also in the socio-cultural sphere. It is telling, in this respect, that even though the economic success of integration has been moderate so far, the populations of individual member states seem to have a largely favorable view of regional integration.  Another major reason is that by joining the union, these states were also accommodating various other interests: the bulk of Kazakhstan’s external trade is currently with Europe, and most of the country’s foreign direct investment is of European, US and increasingly also Chinese origin. Still, for a landlocked state like Kazakhstan, with most of its transportation and energy infrastructure still oriented towards Russia, joining the union was a logical consequence in order to get better access to the global market. Moreover, Kazakhstan hopes to contain Russia within a rules-based organization, fearing that Moscow could one day lay claims to the northern, Russian populated part of Kazakhstan. Armenia joined because of Russian pressure, but also because of promises of cheap energy and protection against Azerbaijan, Armenia’s main antagonist in the conflict over Nagorno Karabakh. Belarus relies to a significant degree on continuous shipment of cheap Russian oil and gas. Russia is the primary destination for labor migration, mostly from the Central Asian members and Armenia, and economically weak countries like Kyrgyzstan and Armenia depend to a large degree on Russian investments and loans from the Eurasian Development Bank (which includes all EAEU members and Tajikistan). Therefore, choosing not to integrate might have resulted in potentially painful Russian punitive actions for each of these four states. To be sure, joining the EAEU put initial stress on the economies of Armenia, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, since they all had significantly lower tariffs and needed to raise these in order to match the higher Russian tariffs; also, hopes of a quick economic upturn was soon followed by initial disillusionment, as the combination of Western sanctions and lower oil prices hit not only the Russian economy, but also the other EAEU member states engaged in trade and economic exchanges with Russia. Also, integration did not always come at a benefit. This was especially the case of Kyrgyzstan, which, instead of exporting more of its agricultural products after joining the common EAEU market, now faced sudden though competition from Kazakh, Russian and Belorussian companies in its own domestic market. However, since the union is now the common framework to regulate economic and trade relations, all members may potentially benefit from deals negotiated through the EAEU with third parties. Conversely, concluding free trade deals with the EAEU may be interesting for these parties too, since the customs union means that duties are only levied once, and that goods can then circulate more or less freely throughout the economic space. The EAEU and China After concluding a first Free Trade Agreement with Vietnam in 2016, the EAEU Supreme Council has prioritized seven further countries with which it seeks to conclude free trade agreements: China, Iran, India, Egypt, Israel, Singapore and Serbia.18 Of these, Iran and China have already signed comprehensive economic agreements, and Singapore a Memorandum of Understanding. In the meanwhile, Jordan, Morocco, the Faroe Islands, Cuba, Mongolia, South Korea, Cambodia, Ecuador, Chile, Peru, and Thailand have signed memoranda of cooperation with the EEC as well. While the most likely future member of the EAEU is Tajikistan, countries including Syria, Tunisia, the Philippines, Pakistan, and Turkey have shown interest in closer cooperation. The EAEU is also engaged in talks to establish cooperation with international organizations, including APEC (of which Russia is a member), ASEAN, the Andean Community, the CIS, Mercosur, as well as several other international organizations. The EAEU also seeks official observer status at the WTO, but has so far failed to establish formal relations with the European Union. After the signing of a provisional free trade agreement with Iran in May 2018 with the purpose to form a full-scale free trade area in the future, the EAEU has also, in May 2018, reached an agreement on economic and trade cooperation with China. The deal with China could be of great importance should this indeed pave the way to the conclusion of a comprehensive Free Trade Agreement. The two sides express their desire to “create the conditions for the development of mutual trade relations” and the “promotion of economic relations.” The EAEU and China are also “[r]ecognizing the importance of conjunction of the Eurasian Economic Union and the Belt and Road initiative as a means of establishing strong and stable trade relations in the region.”19 The purpose of the deal with China is, from a Russian perspective, to contain Chinese influence in the post-Soviet space, in Central Asia in particular, and coordinate policy with other EAEU members. Agreeing on a common position towards China might be in the interest of all EAEU members. Currently, China decides where and in which projects it wants to invest, and directly negotiates with each EAEU member. Over the past seven years, China has invested almost 100 billion USD in EAEU member countries in 168 projects, many of which are part of Beijing’s Belt and Road initiative.20 The bulk of this investment has been directed towards Central Asia. While Kazakhstan has been the largest recipient of Chinese investment in absolute terms, China’s engagement also has a significant economic impact on smaller and less diversified economies. In Kyrgyzstan, for example, China’s share of the country’s foreign direct investment has increased to 37 percent, and China accounts for 28 percent in Kyrgyzstan’s total trade turnover. Due to large loans for various projects, China holds 41 percent of Kyrgyzstan’s external debt.21 Kyrgyzstan’s possible financial dependence highlights the risk small economies face when incurring too much debt. But larger countries also feel uneasy about China: While Kazakhstan’s political elite emphasizes political sovereignty, there is an understanding that the alliance with Russia serves as a counterbalance to China’s growing presence in the region, which is felt also through the large number of Chinese migrant workers or cheap Chinese goods undercutting domestic producers.22 Moreover, as important as recent Chinese financial assistance and investments are to the Central Asian states, there is a danger that these states are building projects which might benefit long-term Chinese economic interests, but not the states in question. Given China’s economic might, and since all the states of the region are in need of investment, Beijing’s negotiating position is strong. As a result, EAEU member states sell their goods on terms mostly favorable to China. This includes natural resources, which the region has in abundance, as well as agriculture, which has become increasingly important. Since China has increased the import of agricultural products, agreeing on a common policy might be in the interest of the EAEU. The EAEU framework could also be used to harmonize certain standards, as this might stimulate business cooperation and remove bureaucratic red tape. Direct dialogue between the EAEU and China will not replace bilateral links; rather, the EAEU might help to facilitate better mutual relations, and improve the EAEU members’ negotiating position. Moreover, if the EAEU concludes free trade agreements with other important Asian states, namely India, this would open other markets and reduce the risk of overdependence on China. In sum, should Russia manage to convince EAEU members to agree on common policies towards China (and other third states) this could be to the benefit of each country. However, it would also mean more commitment and coordination among the EAEU member states, which would draw them further into the Russian orbit. Russia, the EAEU and Europe While China and other Asian states have been willing to cooperate with the EAEU, much of the EAEU’s success will ultimately depend on the European Union’s attitude. Notwithstanding the growing economic importance of Asia, the European Union still is the EAEU’s biggest trading partner, accounting for about half of the EAEU’s total exports, and about 40 percent of its imports (though the share of imports from the larger Asia-Pacific region is now higher than from the European Union). Moscow has therefore been pushing for the establishment of formal relations between the EAEU and Brussels, and the conclusion of a free trade agreement is one of the declared goals of the EEC’s foreign policy. Brussels has rejected formal dialogue with the EAEU, largely for political reasons. It is reluctant to provide legitimacy to an organization dominated by authoritarian states. Also, Brussels is loath to establish relations with a union seen to be controlled by Russia. Formal recognition of the EAEU would mean increasing cooperation with Russia, a country against which the European Union and other Western states have imposed sanctions due to Moscow’s aggressive actions against Ukraine. In a November 2015 letter to Vladimir Putin, EU Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker tied recognition of the EAEU to the implementation of the Minsk agreements.23 Brussels still perceives the EAEU as Russia’s geopolitical tool, and seeks to develop ties with states in the region along bilateral lines.  To be sure, Russia is the dominant power within the EAEU. But it would be wrong to see this union as a purely Russian-controlled organization, as Russia cannot simply impose its will on the other members. However, since EU membership is currently out of the question for most of the post-Soviet states, the EAEU is the only alternative. As the EAEU has been slowly but steadily forming an internal market, and economic and trade policy increasingly falls under the jurisdiction of the union, the maneuvering room of individual states, especially when it comes to foreign trade affairs, has been shrinking. Also, by successfully forging international cooperation agreements, the EAEU is emerging as a more visible international actor, and the role of its permanent bodies, namely the EAEU’s Commission, is growing. All of this means that the EAEU is unlikely to fall apart any time soon. While other states and regional organizations, including China, have begun to acknowledge these new realities, the Europeans have been standing aside, thereby risking to lose out on potential opportunities for trade, foreign investment, exchange of know-how and technology transfer. In economic terms, Brussels and the EAEU would benefit from lowering trade barriers and harmonizing technical standards. A study prepared in 2016 on behalf of the Bertelsmann Stiftung predicts a substantial increase in mutual trade if trade barriers between the EU and the EAEU are lowered as part of a free trade agreement; eastern EU members, most of all the Baltic states, but also Slovakia, Finland, Poland, or Germany, would profit significantly from freer trade.24 Coordination would also be fruitful when it comes to the creation of a common EAEU-wide energy market. Europe is a key consumer of Russian and Kazakh oil and gas, and any changes in the Eurasian energy market will have repercussions for consumers outside the EAEU.25 Moreover, the initiation of a dialogue would give the states in between the two economic areas, namely Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia, a chance to perform the role of intermediaries between the two blocs, instead of becoming geopolitical battle zones. Rapprochement with the EAEU would build confidence on both sides and ease current political tensions. EU sanctions (and Russian counter-sanctions) have hurt Russia, states tied to Russia via the EAEU, and neighbors engaged in trade and economic relations with Russia. Finally, tying the whole Eurasian area more closely together would facilitate better connections between Europe and Asia, as it would improve conditions for transit and trade. Should relations between Russia and Europe improve, the whole dynamic on the Eurasian continent might change to the benefit of all. Europe should take note of the profound changes in its eastern neighborhood and reconsider its stance toward the EAEU. Notes 1 Vladimir Putin, Annual Address State to the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation, 25.04.2005. 2 The SCO originated from the so-called “Shanghai Five”-grouping created in 1996 by the heads of states of China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia and Tajikistan. Uzbekistan became a member in 2001, India and Pakistan in 2017. See also Linda Maduz, Flexibility by Design: The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation and the Future of Eurasian Cooperation , Center for Security Studies, ETH Zurich, 05.2018. 3 Jeronim Perović, “From Disengagement to Active Economic Competition: Russia’s Return to the South Caucasus and Central Asia,” Demokratizatsiya, 13, no. 1 (2005), 61 – 85. 4 Eurasian Economic Commission, Eurasian Economic Integration: Facts and Figures , 2016, 4 – 8. 5 V.V. Putin, “Novyi integratsionnyi proekt dlia Evrazii – budushchee, kotoroe rozhdaetsia segodnia ,” Izvestiia, 03.10.2011. 6 Alec Luhn and Terry Macalister, “Russia Signs 30-Year Deal Worth $400bn to Deliver Gas to China ,” The Guardian, 21.05.2014. 7 Valdai Discussion Club, “Toward the Great Ocean – 5: From the Turn to the East to Greater Eurasia ,” 09.2017, 7 and 12. 8 Kira Latuhina, “Kompas pobeditelei: Proekt ‘Bolshaia Evraziia’ ob’iavlen’ otkrytym,” Rossiiskaia gazeta, 19.06.2016. 9 Andrey Kortunov, “One More Time on Greater Europe and Greater Eurasia,” 03.10.2018. 10 Rilka Dragneva and Kataryna Wolczuk, The Eurasian Economic Union: Deals, Rules and the Exercise of Power, Chatham House, 05.2017, 2. 11 Sean Roberts, “The Eurasian Economic Union: The Geopolitics of Authoritarian Cooperation,” Eurasian Geography and Economics, 58, no. 4 (2007), 418 – 41. 12 Alexander Libman, “Eurasian Economic Union: Between Perception and Reality,” New Eastern Europe, 09.01.2018. 13 Eurasian Economic Union Treaty (Dogovor o Evraziiskom Ekonomicheskom Soiuze). 14 Andreas Metz and Maria Davydchyk, Perspektiven der Zusammenarbeit zwischen der EU und der Eurasischen Wirtschaftsunion (EAWU), Ost-Ausschuss der Deutschen Wirtschaft, 04.2017, 5. 15 Ricardo Giucci and Anne Mdinaradze, “The Eurasian Economic Union: Analysis from a Trade Policy Perspective,” Berlin Economics, 11.04.2018. 16 V. Bordachev and A.S. Skriba, “Russia’s Eurasian Integration Policies,” in: The Geopolitics of Eurasian Economic Integration, London School of Economics IDEAS, 19.06.2014, 18. 17 Riccardo Giucci, “The Eurasian Economic Union: Analysis from a Trade Policy Perspective,” Berlin Economics, 29.05.2018. 18 Interview with EEC Chairman Tirgan Sarkisian: “Glava Kollegii EEK: Garmonizatsiia rynkov sozdast blagopriiatnye usloviia dlia biznesa,” TASS, 26.09.2018. 19 EAEU-China Agreement, 1. 20 Oleg Remyga, “Linking the Eurasian Economic Union and China’s Belt and Road,” Reconnecting Asia, 9.11.2018. 21 All figures for 2016. Marlene Laruelle (ed.), China’s Belt and Road Initiative and its Impact on Central Asia, The George Washington University, 2018, viii-ix. 22 Zhenis Kembayev, “Development of China–Kazakhstan Cooperation,” Problems of Post-Communism, 2018. 23 Martin Russell, Eurasian Economic Union: The Rocky Road to Integration, European Parliamentary Research Service, 04.2017, 12. 24 Christian Bluth, Eine Freihandelszone von Lissabon bis Wladiwostok: Ein Mittel für Frieden und Wohlstand: Die Effekte einer Freihandelszone zwischen der EU und Eurasischen Region, Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2016. 25 Maria Pastukhova and Kirsten Westphal, “Die Eurasische Wirtschaftsunion schafft einen Energiemarkt– die EU steht abseits,” Stiftung für Wissenschaft und Politik, 01.2008. Source: Ocnus.net 2019 |